1.2 Elements of Programming

A programming language is more than just a means for instructing a computer to perform tasks. The language also serves as a framework within which we organize our ideas about computational processes. Programs serve to communicate those ideas among the members of a programming community. Thus, programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.

When we describe a language, we should pay particular attention to the means that the language provides for combining simple ideas to form more complex ideas. Every powerful language has three such mechanisms:

- primitive expressions and statements, which represent the simplest building blocks that the language provides,

- means of combination, by which compound elements are built from simpler ones, and

- means of abstraction, by which compound elements can be named and manipulated as units.

In programming, we deal with two kinds of elements: functions and data. (Soon we will discover that they are really not so distinct.) Informally, data is stuff that we want to manipulate, and functions describe the rules for manipulating the data. Thus, any powerful programming language should be able to describe primitive data and primitive functions, as well as have some methods for combining and abstracting both functions and data.

1.2.1 Expressions

Having experimented with the full Python interpreter in the previous section, we now start anew, methodically developing the Python language element by element. Be patient if the examples seem simplistic — more exciting material is soon to come.

We begin with primitive expressions. One kind of primitive expression is a number. More precisely, the expression that you type consists of the numerals that represent the number in base 10.

>>> 42

42

Expressions representing numbers may be combined with mathematical operators to form a compound expression, which the interpreter will evaluate:

>>> -1 - -1

0

>>> 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + 1/128

0.9921875

These mathematical expressions use infix notation, where the operator (e.g., +, -, *, or /) appears in between the operands (numbers). Python includes many ways to form compound expressions. Rather than attempt to enumerate them all immediately, we will introduce new expression forms as we go, along with the language features that they support.

1.2.2 Call Expressions

The most important kind of compound expression is a call expression, which applies a function to some arguments. Recall from algebra that the mathematical notion of a function is a mapping from some input arguments to an output value. For instance, the max function maps its inputs to a single output, which is the largest of the inputs. The way in which Python expresses function application is the same as in conventional mathematics.

>>> max(7.5, 9.5)

9.5

This call expression has subexpressions: the operator is an expression that precedes parentheses, which enclose a comma-delimited list of operand expressions.

The operator specifies a function. When this call expression is evaluated, we say that the function max is called with arguments 7.5 and 9.5, and returns a value of 9.5.

The order of the arguments in a call expression matters. For instance, the function pow raises its first argument to the power of its second argument.

>>> pow(100, 2)

10000

>>> pow(2, 100)

1267650600228229401496703205376

Function notation has three principal advantages over the mathematical convention of infix notation. First, functions may take an arbitrary number of arguments:

>>> max(1, -2, 3, -4)

3

No ambiguity can arise, because the function name always precedes its arguments.

Second, function notation extends in a straightforward way to nested expressions, where the elements are themselves compound expressions. In nested call expressions, unlike compound infix expressions, the structure of the nesting is entirely explicit in the parentheses.

>>> max(min(1, -2), min(pow(3, 5), -4))

-2

There is no limit (in principle) to the depth of such nesting and to the overall complexity of the expressions that the Python interpreter can evaluate. However, humans quickly get confused by multi-level nesting. An important role for you as a programmer is to structure expressions so that they remain interpretable by yourself, your programming partners, and other people who may read your expressions in the future.

Third, mathematical notation has a great variety of forms: multiplication appears between terms, exponents appear as superscripts, division as a horizontal bar, and a square root as a roof with slanted siding. Some of this notation is very hard to type! However, all of this complexity can be unified via the notation of call expressions. While Python supports common mathematical operators using infix notation (like + and -), any operator can be expressed as a function with a name.

1.2.3 Importing Library Functions

Python defines a very large number of functions, including the operator functions mentioned in the preceding section, but does not make all of their names available by default. Instead, it organizes the functions and other quantities that it knows about into modules, which together comprise the Python Library. To use these elements, one imports them. For example, the math module provides a variety of familiar mathematical functions:

>>> from math import sqrt

>>> sqrt(256)

16.0

and the operator module provides access to functions corresponding to infix operators:

>>> from operator import add, sub, mul

>>> add(14, 28)

42

>>> sub(100, mul(7, add(8, 4)))

16

An import statement designates a module name (e.g., operator or math), and then lists the named attributes of that module to import (e.g., sqrt). Once a function is imported, it can be called multiple times.

There is no difference between using these operator functions (e.g., add) and the operator symbols themselves (e.g., +). Conventionally, most programmers use symbols and infix notation to express simple arithmetic.

The Python 3 Library Docs list the functions defined by each module, such as the math module. However, this documentation is written for developers who know the whole language well. For now, you may find that experimenting with a function tells you more about its behavior than reading the documentation. As you become familiar with the Python language and vocabulary, this documentation will become a valuable reference source.

1.2.4 Names and the Environment

A critical aspect of a programming language is the means it provides for using names to refer to computational objects. If a value has been given a name, we say that the name binds to the value.

In Python, we can establish new bindings using the assignment statement, which contains a name to the left of = and a value to the right:

>>> radius = 10

>>> radius

10

>>> 2 * radius

20

Names are also bound via import statements.

>>> from math import pi

>>> pi * 71 / 223

1.0002380197528042

The = symbol is called the assignment operator in Python (and many other languages). Assignment is our simplest means of abstraction, for it allows us to use simple names to refer to the results of compound operations, such as the area computed above. In this way, complex programs are constructed by building, step by step, computational objects of increasing complexity.

The possibility of binding names to values and later retrieving those values by name means that the interpreter must maintain some sort of memory that keeps track of the names, values, and bindings. This memory is called an environment.

Names can also be bound to functions. For instance, the name max is bound to the max function we have been using. Functions, unlike numbers, are tricky to render as text, so Python prints an identifying description instead, when asked to describe a function:

>>> max

<built-in function max>

We can use assignment statements to give new names to existing functions.

>>> f = max

>>> f

<built-in function max>

>>> f(2, 3, 4)

4

And successive assignment statements can rebind a name to a new value.

>>> f = 2

>>> f

2

In Python, names are often called variable names or variables because they can be bound to different values in the course of executing a program. When a name is bound to a new value through assignment, it is no longer bound to any previous value. One can even bind built-in names to new values.

>>> max = 5

>>> max

5

After assigning max to 5, the name max is no longer bound to a function, and so attempting to call max(2, 3, 4) will cause an error.

When executing an assignment statement, Python evaluates the expression to the right of = before changing the binding to the name on the left. Therefore, one can refer to a name in right-side expression, even if it is the name to be bound by the assignment statement.

>>> x = 2

>>> x = x + 1

>>> x

3

We can also assign multiple values to multiple names in a single statement, where names on the left of = and expressions on the right of = are separated by commas.

>>> area, circumference = pi * radius * radius, 2 * pi * radius

>>> area

314.1592653589793

>>> circumference

62.83185307179586

Changing the value of one name does not affect other names. Below, even though the name area was bound to a value defined originally in terms of radius, the value of area has not changed. Updating the value of area requires another assignment statement.

>>> radius = 11

>>> area

314.1592653589793

>>> area = pi * radius * radius

380.132711084365

With multiple assignment, all expressions to the right of = are evaluated before any names to the left are bound to those values. As a result of this rule, swapping the values bound to two names can be performed in a single statement.

>>> x, y = 3, 4.5

>>> y, x = x, y

>>> x

4.5

>>> y

3

1.2.5 Evaluating Nested Expressions

One of our goals in this chapter is to isolate issues about thinking procedurally. As a case in point, let us consider that, in evaluating nested call expressions, the interpreter is itself following a procedure.

To evaluate a call expression, Python will do the following:

- Evaluate the operator and operand subexpressions, then

- Apply the function that is the value of the operator subexpression to the arguments that are the values of the operand subexpressions.

Even this simple procedure illustrates some important points about processes in general. The first step dictates that in order to accomplish the evaluation process for a call expression we must first evaluate other expressions. Thus, the evaluation procedure is recursive in nature; that is, it includes, as one of its steps, the need to invoke the rule itself.

For example, evaluating

>>> sub(pow(2, add(1, 10)), pow(2, 5))

2016

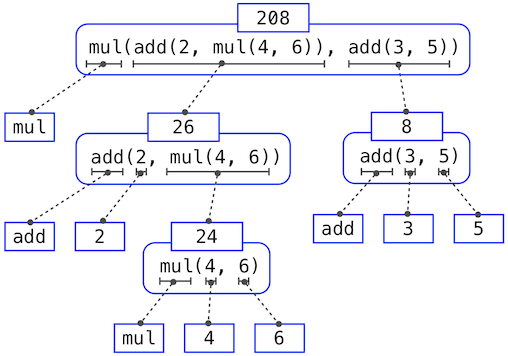

requires that this evaluation procedure be applied four times. If we draw each expression that we evaluate, we can visualize the hierarchical structure of this process.

This illustration is called an expression tree. In computer science, trees conventionally grow from the top down. The objects at each point in a tree are called nodes; in this case, they are expressions paired with their values.

Evaluating its root, the full expression at the top, requires first evaluating the branches that are its subexpressions. The leaf expressions (that is, nodes with no branches stemming from them) represent either functions or numbers. The interior nodes have two parts: the call expression to which our evaluation rule is applied, and the result of that expression. Viewing evaluation in terms of this tree, we can imagine that the values of the operands percolate upward, starting from the terminal nodes and then combining at higher and higher levels.

Next, observe that the repeated application of the first step brings us to the point where we need to evaluate, not call expressions, but primitive expressions such as numerals (e.g., 2) and names (e.g., add). We take care of the primitive cases by stipulating that

- A numeral evaluates to the number it names,

- A name evaluates to the value associated with that name in the current environment.

Notice the important role of an environment in determining the meaning of the symbols in expressions. In Python, it is meaningless to speak of the value of an expression such as

>>> add(x, 1)

without specifying any information about the environment that would provide a meaning for the name x (or even for the name add). Environments provide the context in which evaluation takes place, which plays an important role in our understanding of program execution.

This evaluation procedure does not suffice to evaluate all Python code, only call expressions, numerals, and names. For instance, it does not handle assignment statements. Executing

>>> x = 3

does not return a value nor evaluate a function on some arguments, since the purpose of assignment is instead to bind a name to a value. In general, statements are not evaluated but executed; they do not produce a value but instead make some change. Each type of expression or statement has its own evaluation or execution procedure.

A pedantic note: when we say that "a numeral evaluates to a number," we actually mean that the Python interpreter evaluates a numeral to a number. It is the interpreter which endows meaning to the programming language. Given that the interpreter is a fixed program that always behaves consistently, we can say that numerals (and expressions) themselves evaluate to values in the context of Python programs.

1.2.6 The Non-Pure Print Function

Throughout this text, we will distinguish between two types of functions.

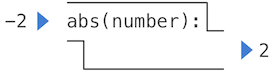

Pure functions. Functions have some input (their arguments) and return some output (the result of applying them). The built-in function

>>> abs(-2)

2

can be depicted as a small machine that takes input and produces output.

The function abs is pure. Pure functions have the property that applying them has no effects beyond returning a value. Moreover, a pure function must always return the same value when called twice with the same arguments.

Non-pure functions. In addition to returning a value, applying a non-pure function can generate side effects, which make some change to the state of the interpreter or computer. A common side effect is to generate additional output beyond the return value, using the print function.

>>> print(1, 2, 3)

1 2 3

While print and abs may appear to be similar in these examples, they work in fundamentally different ways. The value that print returns is always None, a special Python value that represents nothing. The interactive Python interpreter does not automatically print the value None. In the case of print, the function itself is printing output as a side effect of being called.

A nested expression of calls to print highlights the non-pure character of the function.

>>> print(print(1), print(2))

1

2

None None

If you find this output to be unexpected, draw an expression tree to clarify why evaluating this expression produces this peculiar output.

Be careful with print! The fact that it returns None means that it should not be the expression in an assignment statement.

>>> two = print(2)

2

>>> print(two)

None

Pure functions are restricted in that they cannot have side effects or change behavior over time. Imposing these restrictions yields substantial benefits. First, pure functions can be composed more reliably into compound call expressions. We can see in the non-pure function example above that print does not return a useful result when used in an operand expression. On the other hand, we have seen that functions such as max, pow and sqrt can be used effectively in nested expressions.

Second, pure functions tend to be simpler to test. A list of arguments will always lead to the same return value, which can be compared to the expected return value. Testing is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Third, Chapter 4 will illustrate that pure functions are essential for writing concurrent programs, in which multiple call expressions may be evaluated simultaneously.

By contrast, Chapter 2 investigates a range of non-pure functions and describes their uses.

For these reasons, we concentrate heavily on creating and using pure functions in the remainder of this chapter. The print function is only used so that we can see the intermediate results of computations.

Continue: 1.3 Defining New Functions